Food Allergy Recognizing and Responding to Symptoms

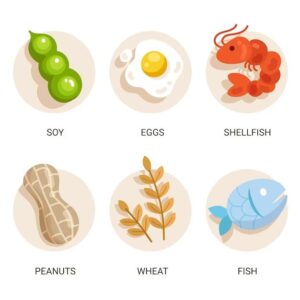

Most often, negative reactions to food items, from anaphylaxis, and lactose intolerance, to gluten hypersensitivity and food poisoning, are usually grouped under the umbrella of “food allergies.” To prevent confusion, we will limit food allergies to reactions that have an immunological cause, i.e., to inflammation-related diseases that affect the immune system. This includes IgE antibodies that cause immediate reactions to food. Even so, certain illnesses, such as eosinophilic esophagitis and celiac diseases, are not mediated by IgE. enterocolitis brought on by protein consumption. Food allergies can impact the skin, gastrointestinal system, and respiratory system, among other organs. Reactions may be fatal, especially if they impact the neurological or cardiac systems (anaphylactic shock). In the high-income nations where allergies are commonplace, the number of cases such as food allergies and other food items, has increased in the past few decades, an increase that is being observed in emerging economic systems. Environmental changes, increasing urbanization, climate change, reduced exposure to infections in the early years of life,, as well as changes to lifestyle and eating habits, all play a role in this trend. Eczema and food allergy are typically the first signs of allergies, which manifest at a very early age, typically in the very first year of the life span. This is thought to be the beginning of what is known as the allergic march. the phenotype of allergy with time develops into respiratory manifestations like allergic rhinitis or allergic asthma caused by exposure to the indoor environment (house dust mites and pets or molds as well as cockroaches) as well as outdoor pollen (mainly pollen). Pollen allergies, in particular, cause an even greater increase in food allergy due to IgE cross-reactivity. Food allergies are extremely detrimental to the health of patients as well as their carers. In the past, the sole remedy was to avoid exposure or, in the event of accidental exposure, rescue medications. New scientific advances have created fascinating new avenues for diagnosis, prevention, management, and even treatment. What are the major problems in research on food allergies and treatment?

When do food allergies appear, and what can we do to avoid them?

The traditional model of sensitization to food allergies that occur through the oral route has been shifted in favor of alternate routes like the skin, or perhaps those airways. Numerous epidemiological studies have placed the skin at the forefront of the spotlight. In the beginning, we observed that the use of ointments with peanut oil increased the chance of developing peanut allergies. Food allergies were discovered to be linked with SNPs that affect the protein that forms a skin barrier called filaggrin, which can cause impairment in the barrier’s functioning. Then, it was reported that the peanut allergen found in dust was linked to the formation of peanut allergies, but only for those with the loss-of-function-SNPs that encode for the filaggrin. Sensitization of the skin is likely to play an essential role in the development and progression of allergies. However, it is not assumed that sensitization occurs through the respiratory tract. There’s some evidence suggesting that mutations in the filaggrin gene cause allergies within the airways too). If the oral route is responsible for sensitization to foods in any way, this is a subject of contention, however, the standard programming of the oral route is towards tolerance and is suitable for the demands of. To develop strategies that effectively stop food allergies, improved knowledge of the relative significance of different routes for sensitization is paramount. In the long run, the recommendation to atopic parents has been to prevent exposing their children to household dust mites as well as pets whenever possible. It turned out to be more complicated or, in some cases, counterproductive. In the case of children who may be at risk of becoming food allergic, when they experience eczema during the early years of their lives, The idea has for a long time been to hold off the introduction of food items that contain solids, particularly those that are known to be extremely allergic, like peanuts. The first flaws in the idea of a delayed introduction emerged from research comparing Jewish communities in Israel as well as London. A high level of exposure in the early years to peanuts has resulted in the lowest prevalence of allergy to peanuts in comparison to London, where delayed introduction was a standard procedure. The result was the landmark LEAP intervention study that proved the importance of the early introduction of peanuts to prevent the development of an allergy to peanuts among a population at risk. Others have taken place, particularly with eggs and peanuts, with some showing protection, while others have not been effective. However, despite being viewed as an underlying risk early exposure to oral toxins is emerging as a potential avenue of prevention in the primary (and additional?) prevention. However, the inconsistent results call for further research. Food allergies in the early years of life, such as eggs, are not a single event. In combination, environmental, (epi)genetic food, diet, and lifestyle factors affect the way that the reaction to food by the immune system can be influenced. The scientific community is aware that the microbiome has a significant role in determining immunity. The route of sensitization to food can determine the type of microbiome in the process, i.e., of the intestines and airways, or the skin. Microbiomes are formed by the method of the newborn baby’s birth, due to food habits (e.g., fresh and processed vs. processed, pasteurized, or unpasteurized., by the season, or not), and exposure to environmental factors such as bacteria and viruses, parasites, the use of antibiotics, and vaccinations. A lot of these factors appear differently in wealthy countries, developing economies, and countries with low incomes. The socioeconomic and cultural divide presents a wealth of opportunities for studying the roles of all those factors that contribute to the development of food allergies and in the search for efficient prevention and treatment strategies.

How is food allergy diagnosed?

The most reliable method to diagnose food allergies can be found in an oral food test (OFC), which is usually double-blind and placebo-controlled (DBPCFC). Recent years have seen the introduction of component-resolved diagnosis (CRD), which has proven to dramatically improve the reliability of out-of-vitro tests, which in turn reduces the necessity of OFCs. The 2S albumins found in legumes (e.g., Ara h 2), as well as tree nuts (e.g., Cor a 14), have been proven to be effective instruments for diagnosing food allergies. It is a matter of contention that CRDs with microarray-like structures are involved in the assessment of people who are suspected of having a food-related allergy. They can provide a complete sensitization test with small amounts of serum, however, their sensitivity is less than that of single-plex CRD. Furthermore, it is possible to argue that they provide a wealth of data that is not requested and can sometimes cause more confusion than facilitate the necessary clarity for the daily routine. As a result of the introduction of CRD for the diagnosis of food allergies, in vitro tests of the biological activities of specific food allergens (IgE, for example, BAT, and the Basophil Activation Test (BAT) are proving high diagnostic efficiency. There is a good chance that the “marriage” between BAT and CRD, e.g., BAT using the purified Ara h2, could enhance the accuracy of diagnosis. The availability of facilities for performing BAT at a non-academic level in daily medical practice could be an obstacle to widespread implementation, which is why the creation of molecular skin prick tests could be a viable solution. Diagnostic tests using molecular technology can assist in the identification of different phenotypes and diseases and, more specifically, in determining the risks associated with severe reactions. Some studies have provided convincing evidence to show the fact that IgE for, e.g., Ara h 2 or Cora 14 can be associated with more serious reactions. However, this was not the case in all the research. It is important to determine the factors by which demographics and clinical characteristics are responsible for the differences observed in the CRD’s performance. A promising new approach for improving the predictive power of the diagnosis of food allergies is to incorporate CRD and clinical and demographic parameters to create a model predictive of the disease. One of the most significant parameters that is associated with mild symptoms is a pollen allergy, which is not seen as a primary sensitization reaction to the molecules that cause serious symptoms. The reason for this “protective” impact is yet to be clarified. It appears that outcomes associated with skin (atopic skin dermatitis throughout existence, signs upon contact with food or substance, and allergies to latex) can be linked to the risk of developing serious reactions. These findings could be explained by the primary source for sensitization to the skin needs of allergies, which makes use of computer-generated algorithms to combine information from various sources. In the age of artificial intelligence and omics, it is anticipated that the combination of biomarkers from the past and modern can further enhance the accuracy of diagnosis.

How Should Food Allergies Be Treated?

AIT to treat respiratory allergies is a proven, effective, and safe treatment, with proof of long-term tolerance in both the subcutaneous as well as sublingual routes. To treat food allergies, oral (OIT), epicutaneous (EPIT), sublingual (SLIT), and subcutaneous (SCIT) treatment options are in various stages that are in the process of developing. The only AIT to treat food allergies that had been approved for commercial use was OIT, which treats peanuts. One of the biggest challenges faced by AIT for food allergies includes the possibility of severe adverse effects, the smaller effect area, and last but not least, there is no evidence of sustained effectiveness. The most serious adverse side effects are linked to OIT. Though the effect size of OIT is very good, however, long-term efficacy after the end of treatment is the only exception, not the norm. In the cases of EPIT and SLIT, the effect sizes are smaller, however, treatment is well tolerated. In the meantime, sustained efficacy has not been fully investigated. To date, for SCIT, there is no data on efficacy that exists yet. The next step is to create a solution that is secure and has long-term efficiency. Based on the data available, there is a clear indication that effectiveness improves when treatments are given to infants rather than adults. Perhaps at a younger age, the immune system remains more receptive to being directed steadily away from allergens and inflammation towards tolerance. This assumption is also supported by LEAP research and early intervention studies conducted by LEAP-ON in children aged 1 to 2 years older who had already been allergic to peanuts and didn’t develop an allergy to peanuts if the peanut was introduced at a young age into life. These findings suggest that extremely young AIT, where sensitization hasn’t yet been translated into the clinical manifestation of food allergy, might be the most likely path to take. What route(s) to administer to succeed the best remains to be determined. Food allergies have increased in frequency, and the highest quality studies that are both basic and transformative are required to reduce their effect on the health of the patients as well as their carers. A better understanding of the causes that are responsible for this rise should draw on the comparative study of affluent nations, emerging economies, and low-income nations. This will aid in developing the most effective preventive and therapeutic approaches. The study of the pathways and processes of sensitization could help identify phenotypes as well as types of food allergies. Advancement in these fields of research is crucial for creating effective strategies for prevention as well as therapeutic alternatives. The early intervention approach has received a lot of praise, but further, it is necessary to confirm this in other communities and also for different foods. Policies for public health will have to be based on research, taking the culture of the population and lifestyle into consideration. The combination of in vitro serological (CRD) as well as cellular (BAT) tests alongside clinical and demographic information to create prediction models could offer a potential method to decrease dependence on DBPCFC to diagnose, however, testing of such methods is crucially required. AIT is rapidly expanding in the field of food allergies, but significant challenges in terms of the safety of AIT and its long-term efficacy will be faced. In addition, the causes and mechanisms behind non-IgE-mediated food allergies need to be further investigated to improve treatments and preventive methods. The food allergy action of Frontiers in allergy is open to high-quality contributions to these and related areas of study that are fascinating.